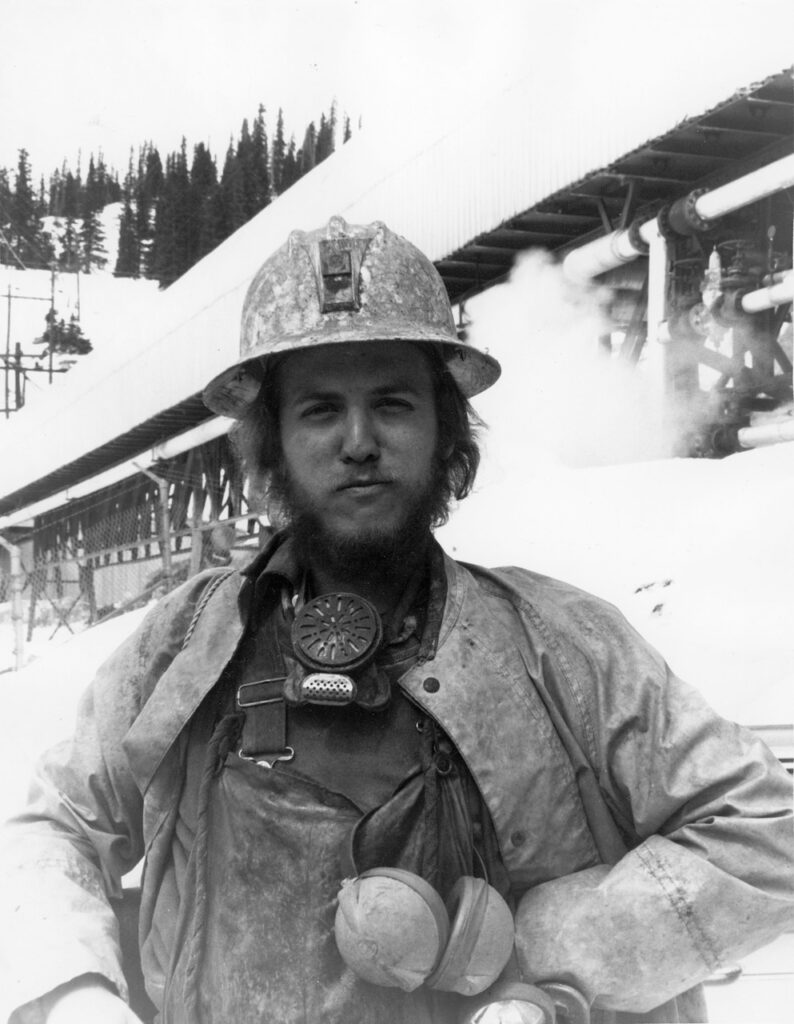

The first time Lucian Childs escaped his Texas life was in 1972 when, after graduating Southern Methodist University, he travelled to Leadville, Colorado and embraced the counter-culture by becoming part of a small hippie community. An historic mining town, rent was cheap in Leadville and some jobs available, but in less than two years Lucian found himself back in Texas, attempting to find a career. The more I have explored Lucian’s life with him the more I have come to sense that underlying tension, conflict, growing up in the 1950s and 60s, his feelings of isolation and loneliness set against a desire to have community, to be productive, and, most of all, to find love. But what community? How to be productive? Where to find love?

As with a number of my writer friends, I met Lucian Childs when Lee Parpart formed the Annex Writing Circle in Toronto. Meeting monthly, each member shared bits of the fiction or poetry they were crafting and everyone provided constructive feedback. In April, 2019, Lucian submitted “The Blessed Ones”, a short story that explored a 1970s Christian gay conversion camp near Waco, Texas. Funny, painful, full of grim irony, the story not only conveyed to me the power of Lucian’s writing but also the depth of experience growing up gay in Texas. I remember being surprised when Lucian stated that he’d never been sent to such a camp but he had spent a year diligently researching those type of facilities to infuse an empathetic story with factual details. Another signal to me of his prowess, and commitment, as a writer.

Born in 1949, Lucian sensed being unlike those around him at an early age. “Before puberty I knew I was different. After puberty, I understood how,” is how he succinctly phrases it. He found himself surrounded by a type of social, political, and religious conservatism one expects in Texas of the 1950s and 60s, including his family who, Lucian says, were “your run-of-the-mill, keep-up-with-the-Joneses middle/upper middle class family. We went to a wealthy Methodist Church, lived in the upscale Park Cities.” For reference, Park Cities encompasses two side-by-side municipalities surrounded by the city of Dallas.

Lucian isolated himself in his bedroom and inhabited a world of stories, reading obsessed. The one social activity he remembers fondly, joining the Cub Scouts, came about simply “because that’s just what boys did back then.” When he went to high school, he continued to immerse himself in fiction, eagerly taking on the ambitious list of novels required by his private school that included tomes such as Anna Karenina and War and Peace. His search for community led to an “intense involvement with the Drama Club and summer stock theatre. I mostly did lights, where night after night I was exposed to the most beautiful language, some of which I can still recite today.” Lucian continued from the Cubs to the Boy Scouts, helped along by one friend he did have at St. Mark’s School for Boys, and the boy’s father, “an extremely dynamic man” who transferred skills he’d learned as a US soldier to a camping program for older boys. Having been part of Merrill’s Marauders, a guerrilla force living behind enemy lines in Burma during the Second World War, his expertise was formidable. “He kindled a love of nature in me that remains very strong to this day,” Lucian remembers. “For a lonely boy with few friends, the camaraderie, the shared hardship with the other guys on our long multi-day hikes, was an important antidote to the isolation I felt at school.”

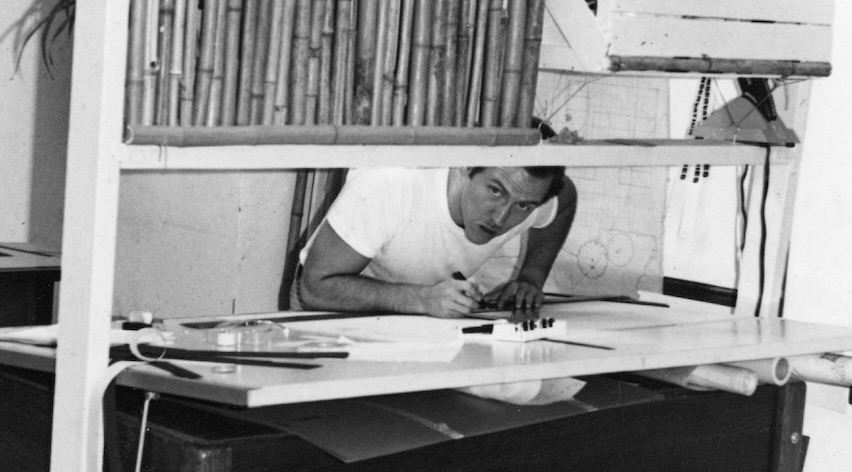

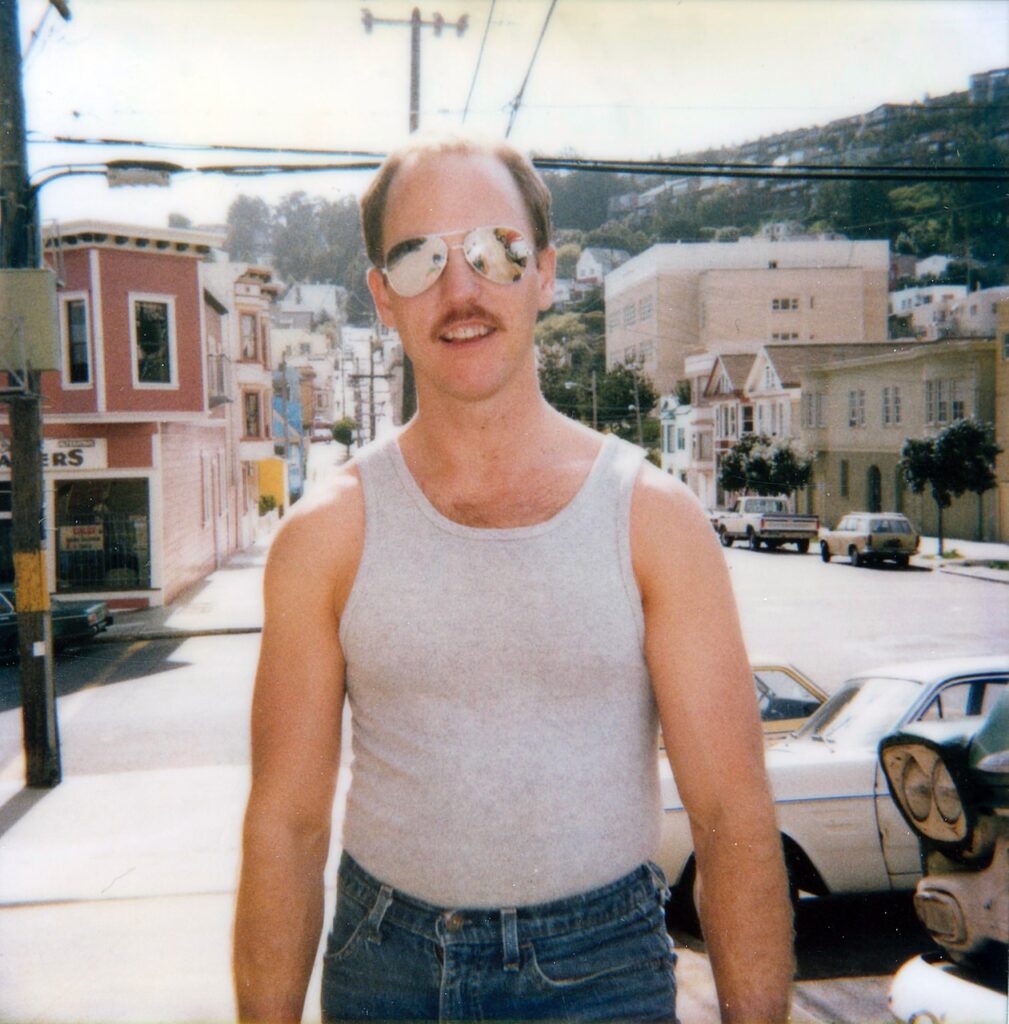

As far as academic skills were concerned, Lucian’s love of literature led him to major in English, not exactly the road to the practical way of life his family expected, the world of professional men: doctors, lawyers, business executives. That need to be a productive member of society delivered him back to Texas from his brief hippie sojourn to spend six years studying at The University of Texas at Austin School of Architecture. During that period his parents died. Lucian was 26 years old and the grief he felt for his lonely childhood became tangled with grief he now felt at parents gone far too young. During his time in Austin, Lucian told me he did come out. That said, even though “Austin had a large, fairly open gay scene, it was surrounded by the parochialism of Texas.” Upon graduation he left Texas behind for good and “pursued my new life as a gay man in San Francisco, while quietly becoming active in zen practice at the San Francisco Zen Centre.”

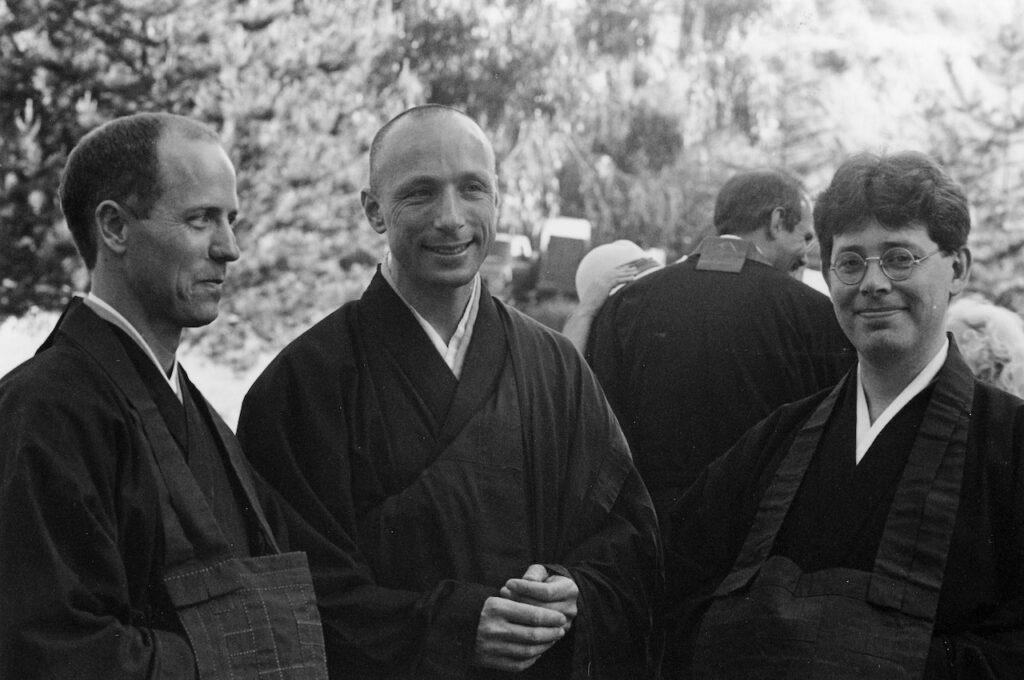

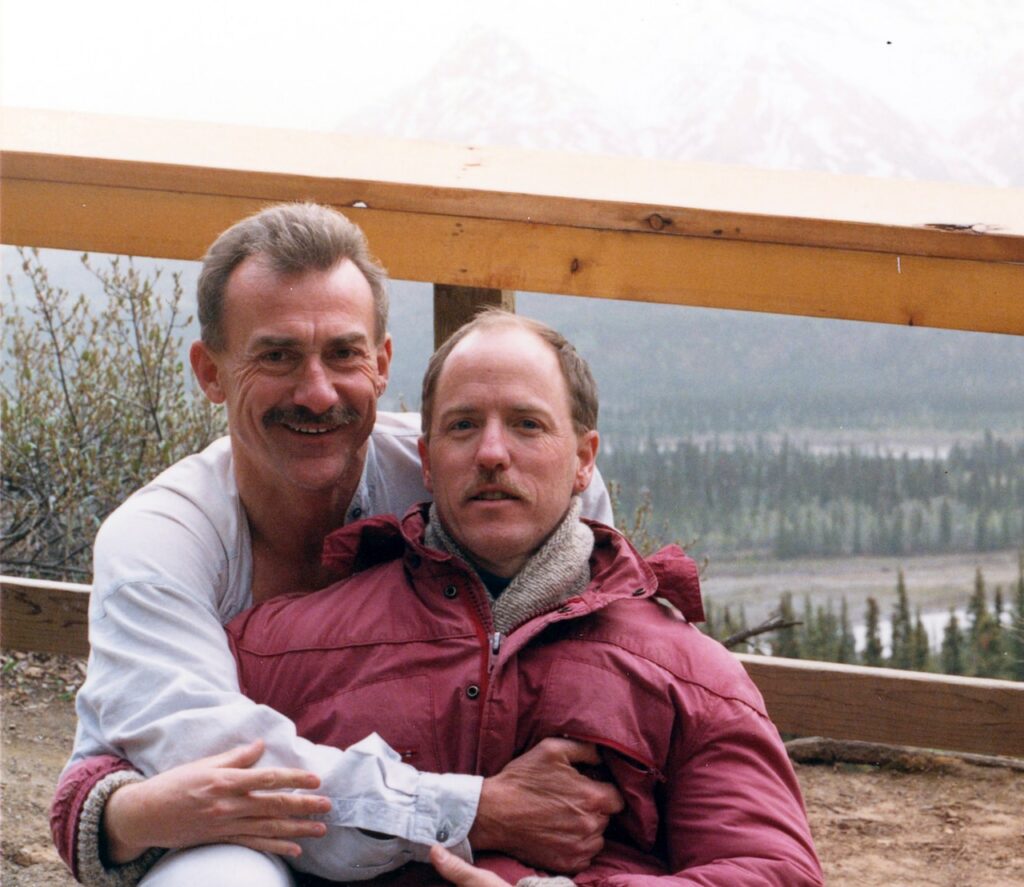

As much as Lucian had enjoyed his time in Austin, learning the history of architecture and design fundamentals, the actual work in San Francisco turned out to be disappointing. He joined a mid-sized firm where hardly anyone designed, most of them working on technical drawings. The university program had provided very little technical training for this and Lucian constantly felt as if he didn’t know what he was doing, wrapped by a sense of panic all the time. In contrast, zen practice brought a new approach to life. The San Francisco Zen Center had bought a large property around the Tassajara Hot Springs, about forty-five miles east of Big Sur, and founded the first Zen monastery outside of Asia. For awhile Lucian was on the priest track but after having fully experienced Zen training he wanted to return to his “gay life in San Francisco” and, at almost forty years old, found his first real love. Paul Cole, a clinical social worker, was, in Lucian’s words, “gorgeous and refined” and it was “love at first sight.” All love affairs present their own difficulties and for Lucian it came with Paul informing him that he wanted to relocate to Alaska after being offered a job in a small town outside of Anchorage. HIV positive, Lucian says Paul “knew the clock was ticking and he wanted a quieter life in a non-urban setting.” It took a couple of years for Lucian to follow, which he did in 1992. Paul began to suffer from acquired immunodeficiency syndrome and died nine months after Lucian arrived.

Although now alone and grief stricken in Anchorage, two interesting turn of events transpired. In order to make money when he first arrived, Lucian says that he “took a job as office support and started designing forms and ads for this guy and a light bulb went off. In 1995 or so, I went out on my own as a freelancer. After two or three very lean years, my design business took off.” After those years studying design, but being disappointed in his San Francisco architectural career, he ended up with a twenty-five year successful graphic design business in Alaska, a place where that love of nature that he’d discovered as a boy could also be fulfilled.

The other turn came a few years later with a return to his boyhood passion for reading. Somewhere along the line after graduating college Lucian had given up reading fiction, but in the early years of this century he became aware of director Ang Lee’s project to bring Annie Proulx’s short story, “Brokeback Mountain” to the screen. Reading that story became a catalyst, first as a return to the love of reading and then to new creativity, writing.

“I was starting to burn out from my heavy graphic design workload and for some reason was beginning to lose my passion for design. Movies take a long time to write, finance, cast, shoot and edit, so in the several years while waiting on the film, I read the short story in The New Yorker and again in Annie’s collection, Wyoming Stories. I poured through that collection and its followup, Bad Dirt: Wyoming Stories 2, and sought out other Western writers. I’d heard of Cormac McCarthy, and started reading him shortly after Annie.” From there Lucian became involved in on-line writing forums and decided that to develop as a writer of prose fiction he needed to focus on the short story.

“I don’t remember reading short stories as a child but I somehow got it in my mind that short stories were the more difficult form. That a writer was supposed to first master the short form before undertaking a novel. People like Updike and Cheever were a kind of model, in that way. I was also reading Alice Munro at the time and I saw in an interview that she figured she’d write novels like everyone else, but started writing short stories because it was something she could fit into the few hours each afternoon while her children were napping. After a while, she got in the habit of seeing stories in this way and abandoned the novel. That’s what happened to me as well. I like the unitary narrative arc and the concision of the short story. Novels meander too much for me and, because they have so much real estate to fill, I find there isn’t always the precision of language that, to me, is the source of fiction’s beauty. Of course, now I’ve stumbled on the novel-in-stories, so I get to have the narrative concision and the verbal precision it requires while still being able to tell a long story.”

When Lucian says he stumbled into novel-in-stories he refers to his first book, Dreaming Home, published in 2023. The short story I’d read in 2019 became the second story in the collection, re-titled as “The Boys at the Ministry”. A striking journey for Lucian, first dabbling in on-line writing forums to a consuming passion for creating short stories. That need for community, need for being productive, which had taken him down different paths throughout his life was fulfilled through an energetic burst of creativity. He became involved in Anchorage’s lively literary scene and travelled to Ohio to attend the Kenyon Review Writers Workshop where he met his first mentor, Nancy Zafris. Lucian flourished with productivity, endured nearly a thousand rejections, but found publication for thirteen short stories by the time he closed up the graphic design business in 2017.

Along the way in this creative journey, beginning with those on-line writing forums, came another love — and ultimately a new grief — in Lucian’s life. Lucian only knew the person as AJT and he’d already been through a relationship with an online writer that left him dubious of persona. That writer, an early writing mentor, claimed to be a former Marine having served in Afghanistan — perhaps shades of the soldier-Scout Leader in Lucian’s boyhood who kindled in him a love of nature — but three years later the “man” disappeared, leaving Lucian to wonder what had been real and what had been on-line persona. Perhaps they were a woman not a man, a speculation that led Lucian to compose his first short story, “Hit Me Back”. As his relationship with AJT evolved, the skepticism remained until he received a photo which prompted Lucian to immediately email in reply, “Dude, you’re a guy!”

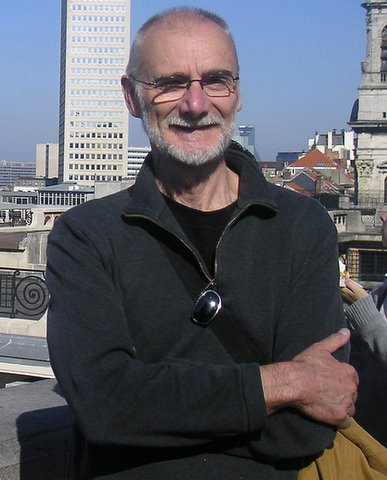

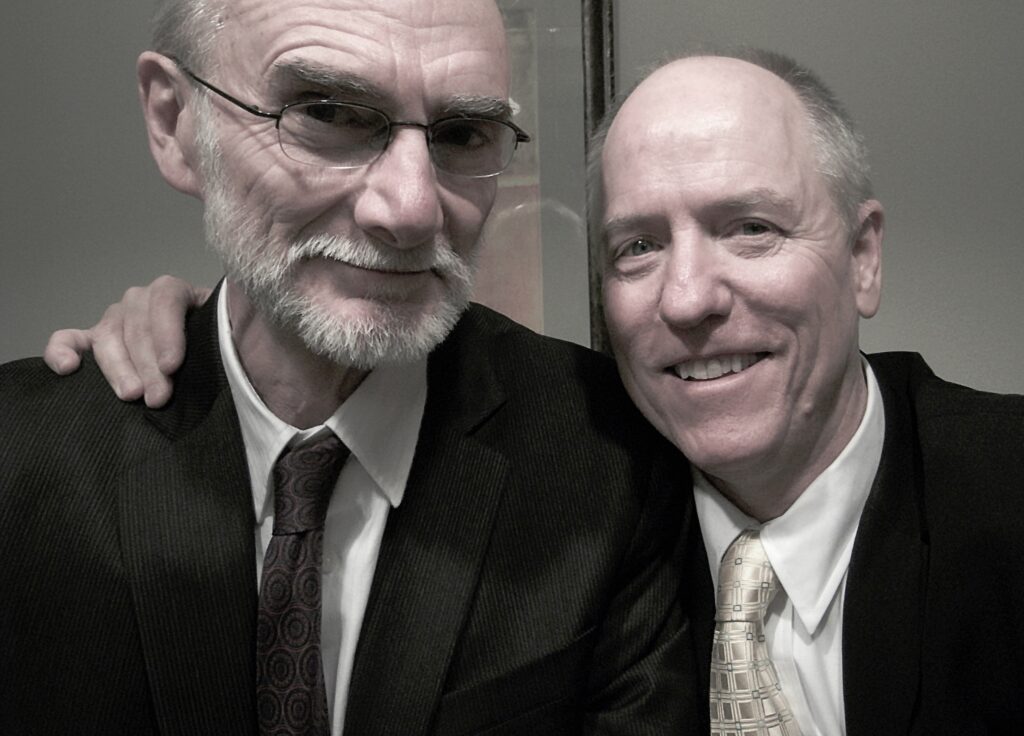

AJT turned out to be the very real Alex Turner, a Toronto based visual artist born and raised in the British Columbia Fraser Valley community of Harrison Hot Springs. To quote Lucian’s opening sentences from his co-author’s note for his next publication, Confluence:

“To fall in love with someone is also to fall in love with their story. For many gay men, this starts right away, over post-coital pillow talk. Sharing tales of the first time we had sex with another man. Or when we finally came out to our families. Where we grew up. What it was like there for gay boys like us. In this way, soon after Alex and I met he started wooing me with stories of his BC boyhood in the ’50s and ’60s.”

He and Alex went back and forth between Anchorage and Toronto for several years, marrying in 2014, and a year later Lucian relocated to Toronto, becoming a Permanent Resident. The life Lucian sought, the sense of community, of being productive through creativity thrived, but its combination with love, a partner to share that artistic life with, proved to be short-lived. In November, 2017, Alex was diagnosed with cancer, dying on May 31, 2019. Lucian remembers the eighteen months in between dominated by chemo treatments — although there was“one trip to Vancouver in the summer of 2018 when he was on a drug holiday and feeling well.”

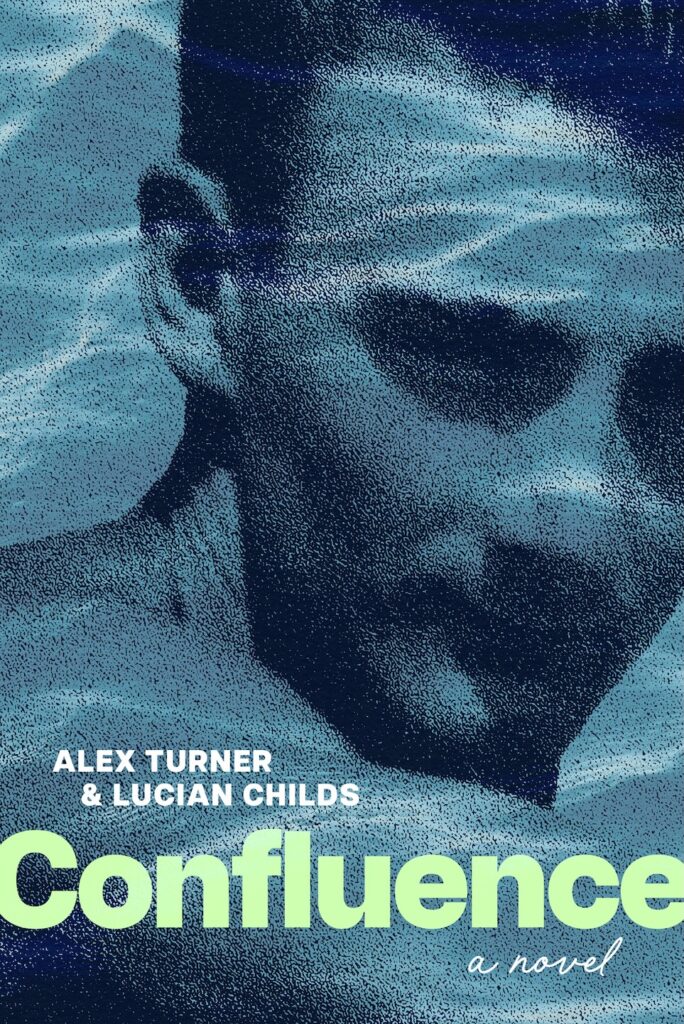

Community, creativity, and love now concurrent with grief. In 2020, he began to work with award winning author Caroline Adderson at the Banff Centre for Arts and Creativity. After Covid shut down the mentorship program, Caroline agreed to continue working with Lucian privately on Zoom for nine months, adapting and linking some his published stories. When they came to the attention of John Metcalf, described by Lucian as “the grand old man of Canadian letters”, he requested stronger linkages and the collection became the “novel-in-stories” published by Biblioasis. With all of that going on, Lucian still dedicated himself to keeping the memory of Alex alive in the world through his art, maintaining a website showcasing Alex’s photograph, writing, and the press he had received. He organized a 2022 retrospective of Alex’s work, “Transformations”, for the Harrison Festival of the Arts, working closely with Rosa Quintana Lillo and her husband, Mike Edwards, Alex’s former students and close friends from his hometown. Much beyond all that, Lucian also took on the duty of finishing and publishing the novel Alex had been working on. While in the hospital his husband had lamented that he wouldn’t be able to finish his first novel and, after a brief pause, said to Lucian, “I guess you’ll have to do it.”

Beginning on the project in 2022, it was clear to Lucian that Alex’s short stories were also in the form of “novel-in-stories”. However, as Lucian stated, “the overarching narrative was underdeveloped, requiring a great deal of rewriting and, in some cases, writing new material. The rule was that I couldn’t make up anything out of whole cloth. It had to come from his life, as recounted in his memoiristic writing, letters, editorial notes, personal recollections and photos from the period.” I have come to know Lucian much better during these last few years after we formed a small group of writers who had once been part of the Annex Writing Circle, not to critique but to converse about, and support, one another’s creative and publishing efforts. During this time, I’ve seen Lucian struggle with how to honour his late husband’s original work while at the same time structure it into something complete and polished for a potential publisher.

The reward for his commitment to honour his late husband’s work, and the dedication to make it the best work possible, arrived with Vancouver based Arsenal Pulp Press agreeing to publish Confluence, a novel-in-stories by Alex Turner and Lucian Childs, in 2026. Working with Arsenal for the final edits and marketing of the novel after publication will consume much of Lucian’s time. But then he will be able to return to his individual work, looking to re-craft old stories and create new ones, for a novel that will have some connection to Dreaming Home, with exploration of a few characters in different stages of their lives.

Lucian recently shared with me an essay he is circulating to literary magazines called “Belated: Reflections on Beginning the Literary Journey Late in Life”. It documents how Lucian found his artistic self at nearly sixty and now, at seventy-six, struggles with internal doubt regarding what more can be accomplished at such a late stage in life, troubled with the nagging question of “why even bother”. Lucian finds hope, or at least a will to continue, through the words of many other writers, including one Charles Bukowski quote: “You either get it down on paper, or jump off a bridge.”

No argument with Bukowski’s sentiment, but I want to point Lucian back to his younger days, the Zen teachings he explored, and remind him that life needs to be lived in the present. Every day Lucian creates something new is a day lived well, no matter age, thirty-six or fifty-six or seventy-six. I want to tell Lucian that he is a damn fine writer who demands of himself to be better and that can still be achieved at eighty-six. I want to tell Lucian all these things — well, maybe I just did.

I’m happy, reader, that you’ve followed me in my return to writing and posting new Profiles. Next up is Bob Oliver, a past Executive Director of Pollution Probe, now an environmental entrepreneur focused on the development of hydrogen fuel as a means to battle climate change by reducing greenhouse emissions.

I hope you come back.