When Bob Oliver left for his first year of engineering at Ottawa’s Carleton University he did so with the intention to live the Animal House experience. Be careful what you wish for. Bob succeeded so well that he realized late in the year he was not going to make the grade. Rather than failing, he met with the Dean of Engineering who offered Bob a solution. If he was serious about studying he could withdraw from the program, re-apply, and then attend first year the upcoming September. He accepted the generous offer and returned with a plan to set himself up for academic success by avoiding distractions. Bob remembers that he rented “a room in a rooming house with no phone or TV. The only common places were the bathroom and kitchen. There were no other students in the house.” His complete turnaround was obvious when he finished the year ranked 5th amongst all first year engineering students. The next year, seeking some social interaction not related to the year of partying, he became involved in student politics as a member of the Engineering Society, and was elected president in his 3rd year. Bob believed the role would help him develop leadership. Well that leadership became forged in fire because, after he became president, the Carleton Students Association announced they were suing the Engineering Society for their misogynistic attitude towards women. Anyone remembering the “good old days” of university engineering newspapers will understand. Bob’s act of leadership was to take a straight forward approach — he owned up to the issues, acknowledged the Students Association was right, and promised the Engineering Society would change their actions going forward. End of the lawsuit.

Born in Toronto in 1969, Bob moved to Brampton at a young age and grew up in the suburbs. His father had been raised in an old coal mining town in Nova Scotia, leaving at sixteen-years-old to move to Toronto where he met the young woman he would marry. Bob’s mother, the youngest of five children, had emigrated with her family to Toronto from Ireland and he remembers an array of ribbons and trophies decorating the house when he was a child. Awards given to his mother who excelled as an Irish step dancer, winning competitions as far away as Boston and New York City. Reflecting back, Bob sees himself as a rather shy kid who was never particularly studious in school, his marks fluctuating with his effort. His father had become a partner in a steel and tube company where he developed great admiration for engineers and it was through his father’s influence that Bob settled on going to engineering school. The choice to attend Carleton was very simple — when he went to Ottawa for a visit he fell in love with the large campus situated between the Rideau Canal and Rideau River.

I first met Bob sometime after he’d succeeded Ken Ogilvie as Executive Director of Pollution Probe. (You can click on the links to earlier Profiles to learn more about Pollution Probe and Ken.) Still working at Union Gas at the time, I’d been asked to serve on a Pollution Probe Advisory Council for their work to develop a primer on Energy Systems Literacy in Canada. I’m sure our paths crossed then and likely during a few other initiatives but I really got to know Bob socially through our mutual friendship with Ken. In a certain circle of dedicated Toronto environmentalists (and one retired gas company guy), there is a much celebrated evening, held roughly once a month — as organized by founder and chair, Ken — known as Wings Night. The state of the world is much discussed over chicken wings and beer, with solutions abounding, though general aspects of planet dissolution owing to environmental destruction are also tolerated as is the eating of salads and drinking of non-alcoholic beverages. One of the things I learned about Bob over many conversations is how he personally changed from an industrial engineer at a large American corporation to an environmental leader focused on the need for transforming energy systems.

After graduating Carleton he took a couple of entry level sales engineering jobs and then accepted a role as an industrial engineer at a large American owned corporation providing a range of products and services to businesses including work apparel — renting uniforms to customers with weekly laundering packaged into the service. A foundational experience. Bob came to understand that the way the plant went about washing the uniforms was driven by a work process that made the hot water use extremely inefficient. He proposed a solution using direct fired water heaters, but it didn’t quite meet the company’s required return-on-investment for capital expenditures, and was deemed nonviable. However, he met an industrial sales representative from Enbridge, the Toronto based natural gas utility, who offered the potential of a financial contribution from their Demand Side Management (DSM) funds. DSM was an Ontario Energy Board required utility program to enable customers to utilize natural gas much more efficiently. The upshot was a financial incentive that helped the project meet the company’s ROI requirements. When the new process was up and running it not only met the planned energy savings but, in re-engineering the old industrial process, the much more efficient approach saved so much money the company mandated the change throughout their American operations. Enbridge approached Bob to participate in a write-up about the success, including the CO2 savings generated, but the company he worked for refused to allow Bob to participate on the grounds that their competitors might learn and implement it themselves. The idea that an environment-improving solution was denied public discourse so offended Bob that he began to look for other opportunities.

About a year before Bob moved on from that company, he and his roommate held a small party that a woman named Linda Klaamas attended. I can’t know for sure but my guess is it might be the first time a discussion about waste water systems (the Toronto Sewers By-Law) led to a first date which led to marriage. Bob felt confident in the specifics of that environmental topic, since it was central to his career, and he quickly learned of Linda’s expertise. A practicing lawyer, she was the sole associate at Saxe Law Office, an environmental boutique law firm whose principal was Dianne Saxe, the legendary Ontario environmental lawyer whose father had been the equally legendary, and crusading, Morton Shulman. Of Dianne Saxe, the idiom does not suffer fools gladly undoubtedly applies and hiring Linda as her sole law associate speaks as succinctly of Linda’s competence as any reading of her resume, which includes graduating Harvard with High Honours in International Environmental Studies, receiving her law degree and Masters of Public Administration at Dalhousie, and a Masters of Laws at The University of Edinburgh. Timing being everything in life, this romantic relationship could not have occurred earlier. As Bob drily told me one day over lunch, “had Linda met me when I wanted to live my Animal House university experience, we never would have gotten together.”

Unhappy at a large corporation for which he’d lost respect, he left and spent a couple of years working with his father in the steel brokerage business. After he and Linda married, Bob followed her to Ottawa when she accepted a job in the federal government’s Climate Change Bureau, and he found a new career path by joining the environmental firm Marbek Resources Consultants. They returned to Toronto in 2003 after Linda was promoted to manager of the Great Lakes Program Renewal. While Bob weighed his employment options, Linda suggested he investigate environmental NGO’s (Non-Government Organizations). He liked what he discovered and began circulating his resume. As things so often work out, the one organization that he did not submit to — in fact was unaware of — contacted him. Someone had passed on his resume to Mary Pattenden of Pollution Probe and, as Bob says, he “found his deep groove” as an environmental professional.

When I reached out to Mary, who I’ve known for a long time as a fellow Wings Night stalwart, though she leans more to the salads and non-alcoholic beverages, she remembered, quite well, hiring Bob in 2004 while she was Pollution Probe’s Director, Climate Change Programme.

“At the time I interviewed Bob, I was looking for a Project Manager to work on Motor Vehicle Fuel Efficiency. I needed someone with a strong technical background. I can’t remember who gave me Bob’s resume, but I was interested when I saw his engineering background. During the interview, Bob was very direct about what he considered his strengths and weaknesses related to the project. If I remember correctly, this would be the first time he would write a major report and he was concerned about this. But, for me, it was obvious he had the technical skills, was quite articulate, organized in his thinking, and that he really cared about doing the job right. So, I hired him.” After she got to know him, another thing she liked was that “he was very, very funny. When he would hand me a draft of the report to edit, he would imbed some of his own comments on the content – which I then had to make sure I found and deleted. It kept me entertained while I waded through the 250 pages.”

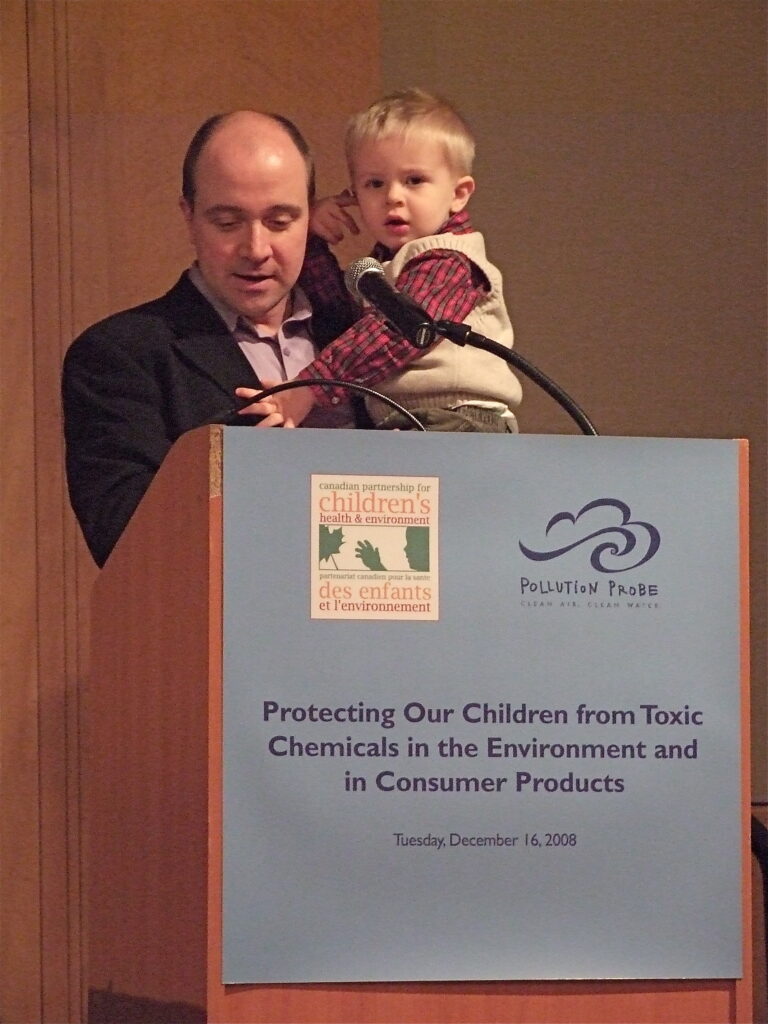

During four years at Probe, before the Board of Directors hired him in 2008 to be the Executive Director, Bob developed an expertise and industry wide reputation. In the words of Ken, the man he succeeded, “Bob did a spectacular job on transportation. His technological/technical talents and his ability to engage with and relate to industry and government employees put Pollution Probe in a great position to move progressive standards forward, despite enormous pushback by elements of the auto sector. He researched extremely well and connected strongly with key staff of transportation companies and governments.” As regards the actual hiring process that elevated him to the position of Executive Director, Maria Kelleher, one of Probe’s board members who was on the hiring team at the time, told me “Bob entered the race late, so he was our final candidate. He had been working with Probe, so really knew the issues, but had initially not applied for the ED position. He blew us away at the interview…we were all in agreement and Bob got the job.”

Despite his continued focus on technical expertise once he became the Executive Director, the real demands of NGO leadership are fund raising and budgeting. The political landscape changed at the time of him becoming Probe’s ED with the Harper government gutting funds in the environmental sector and the Ontario e-Health scandal creating a funding moratorium while they proceeded with internal audits.

“Those two levels of government represented the majority of Probe’s income at the time,” Bob recalls, “and when the revenues ceased, we took a major financial hit. We accumulated significant losses while I scrambled to pivot to other funding sources, mainly the private sector. I spent the next several years working to raise revenues while reducing our deficit of cash.” What Bob feared most about being in the leadership role came about in having to manage budgets by trimming staff. “Worst time of my life,” he noted, “letting people go, long term people who had contributed so much to Pollution Probe.” But he hung in there and says that “by 2014 we had righted the ship, having posted successive positive margins for three straight years, and we had even built a modest rainy-day fund. At that point I faced a decision: lean in for another decade and try to grow the organization to the next level or step aside and make space for new leadership, equipped with a clean balance sheet. I chose the latter and orchestrated my exit with the close of 2015.”

The expertise Bob had built in the transportation sector included a focus on the potential of hydrogen as a means for de-carbonizing transportation sector energy use. Back when he’d worked with his father in the steel brokerage business, Bob had registered a company that he continued to use to bill his time as a contract employee, first with Marbek, and then later with Probe before they hired him as full-time staff. Upon leaving Probe, he revised the company with Linda, named it Tech K.O., with him listed as CEO and her as President. Bob related to me that years before, after their son was born, they’d come to a decision that Linda “would leave government and stay home with Thomson. I should clarify that part of the reason was to restore some stability on the home front, but a big part of it was simply her desire to leave government behind. After more than a decade with government, I believe that she would say she had had her fill and was considering other options.”

Bob was serious about the work required in altering energy systems and understood that “information and objective analysis on low-carbon hydrogen systems would be needed to build understanding and help elevate the quality of dialogue among industry, government and civil society. So, two partners and I established H2GO Canada as a registered not-for-profit in 2018, for which we serve as the organization’s Directors.” From there, he and Linda used Tech-K.O. to become a part owner in Change Energy, a company established over thirty years ago, focusing on major fuel-system transitions. I actually worked with one of its principals, Ry Smith, at Union Gas and Bob came to know him during his transportation programme days at Pollution Probe. Since partnering they have gone on to create HONE, with a unique business focus. The company offers mobile hydrogen power as a clean alternative to diesel generators for the film and television industry. (For a bit of insight take a peek at Bob’s quick explanation in this video.)

No different than when Bob was at Pollution Probe, real world politics and the choices that governments make impact how and when progress is made. What made Bob a perfect fit at Pollution Probe, whether in charge of transportation policy development or as leader of the entire organization, was his belief that the best way forward in advancing improvement is through a process of objective inquiry. Environmentalism, as the term applies to Bob, is not about championing prescriptive solutions without evidence of what can work but rather going down a path of inquiry not at all certain where the evidence will lead. As Bob makes clear, his conviction is that “good policy is achieved through open and transparent research and analysis, in which all those having a stake in the outcome can participate.” Today’s extreme civil and political rancour undercuts that approach and Bob finds “policy development too politicized. There is much less room for exploration and discovery, for doubt and learning. Policy outcomes are defined and then pursued by amping-up political momentum. Put simply, I feel that environmentalism in Canada has become partisan, or at least tribal in its composition, and is thus suffering from the same paralyses that afflicts so many aspects of our society and politics.”

So where does that leave not only Bob but also his life and business partner Linda? When I asked him that question, he answered that today’s politics force them to focus less on policy and more on efforts to build tangible systems of sustainability.

“Linda is developing the framework for a new public education and awareness campaign focusing on human-wildlife coexistence in urban Toronto. Meanwhile, I am working with the partners at Change Energy on growing Hone. While our first interest is environmental policy development, Linda and I will spend the next decade in entrepreneur mode, working to build environmental programs and sustainable energy businesses at a community level. I am hopeful that environmentalism in Canada will gradually become more focused on the outcomes and thus more accommodating of a diversity of means, and I would love to eventually get back into the work of civil society groups for whatever working years I have left.”

However things work out in terms of transforming energy systems specifically, and environmental policy more generally, I think it’s safe to say that Bob Oliver has been successful in transforming himself away from that high school kid looking for his Animal House university adventure. I think it’s also safe to say his partnership in life with Linda Klaamas has greatly assisted in that personal transformation.

Next up is Owen Hamlin. Born and raised in L.A., Owen spent a year in Barcelona at the Conservatori Superior de Música del Liceu before returning home to begin recording some of the 300 songs he began writing as a high school student. Now living in Oregon with his girlfriend Alexis, he’s about to release his third album.

I hope you come back.