New Orleans, July 9th, early evening, and we’re walking through the French Quarter. I’m next to Gordon Shadrach, a Toronto elementary school teacher who is growing in prominence as a visual artist, a painter. Ahead of us is my wife, Barb, engaged in conversation with Gordon’s partner, James. In the media, meteorologists are debating whether the newly named storm, Barry, is a tropical depression or a hurricane. For now, whatever its official designation, it’s still at sea and we are dry as we head to the Court of Two Sisters restaurant for an odd birthday celebration. We are celebrating Richard Shadrach’s 60th birthday on the date he was born, hence the oddness, because Richard is not with us — he lost his battle with depression, with PTSD, the previous year. During a smaller celebration that year, back home in Canada on his 59th birthday, he’d declared he wanted to travel again to New Orleans for the Big Six-O; after his death his wife Joanne asked us to honour him by gathering in NOLA. So here are four of us walking to a restaurant where Richard, Joanne, Barb and I had dined during our many previous visits. Joanne is not walking with us; she will catch up after gathering her children and grandchildren at their rental home near Frenchmen Street; like herding cats, she will say.

Gordon is Richard’s brother and his arrival on the art scene was confirmed in 2018 when the Royal Ontario Museum (ROM) selected him as one of nine artists in their exhibition Here We Are Here: Black Canadian Contemporary Art. That exhibition comes up in our conversation while we walk, to a degree, in that Gordon uses it as a reference point regarding the continuing lack of diversity, the continuing dismissal of black artists by the Canadian art community. There is a tiredness, an exasperation, in his voice as he details a battle he’d had the previous year with the selection committee at the Toronto Outdoor Art Fair, billed as Canada’s largest and longest running juried outdoor contemporary art fair. After three years of rejection, Gordon had been selected to participate in 2017, only to be rejected again in 2018. In the same year where he’s one of only nine artists to be selected for a landmark exhibition at the ROM, he’s not selected as one of over 350 participants at the Art Fair? Of which, by his count, merely includes five black artists, less than two per cent of all artists represented.

I don’t say much. I listen. And I think of the confusion that must swirl through Gordon’s mind. Before all else there is Richard’s death, his closest sibling (there are two other brothers, estranged, not with us in New Orleans). Although he is participating in the 2019 Toronto Art Fair, it comes after a year-long correspondence by Gordon which no one on the Art Fair team ever acknowledged or answered — hence Gordon’s tiredness, exasperation. On the other hand, before travelling to New Orleans, Gordon had attended a ceremony in his hometown of Brampton where it was officially announced that his late father, John, an educator and city councillor, was being honoured with a new street named after him: John Shadrach Way.

John Shadrach arrived in Ontario, from Trinidad, in 1965. His wife, Irma, followed early the next year with two of their three boys (including Richard, the oldest). The youngest boy, at the time, stayed behind with a grandmother while the rest of the family settled. The “rest of the family” grew in October, 1966, when Gordon became the only Shadrach born in Canada. Both parents were teachers and John was the first person of colour to sit on the Brampton City Council. Although it is tempting to say that Gordon followed his parents’ path into teaching, to do so would be to obscure his circuitous path to where he is now, as both teacher and painter.

After graduating secondary school, Gordon attended the Ontario College of Art and Design (OCAD), but not in fine arts, he did very little study of painting. Gordon’s focus was on textiles, within Material Arts and Design. He first left OCAD in 1994 (he would return in 2002 to complete his degree) and worked in visual display for a number of companies such as Polo Ralph Lauren, Harry Rosen, and MAC Cosmetics. At each position he worked on visual elements using his background and interest in design. At MAC he worked on product displayers but was also involved in developing float concepts, designs, and the implementation/building of floats for various gay pride celebrations in North America. Along the way he met his partner, James, who in 2000 was entering teacher’s college. With James’ encouragement, and the recognition of his parents’ calling, Gordon obtained a Masters in Education and joined the Toronto District School Board in 2005. Sometime later he and James bought a townhouse together in Leslieville, not far north of Queen Street, and married.

Now November, I’m sitting in their Leslieville townhouse, at the long wood bench table in the kitchen. At some point in New Orleans I broached the idea of writing this Profile, having recently committed myself to building and launching my website. With the obligations of several exhibitions on the way, Gordon was immersed in painting, and the return of school in September, thus the four months of time passage before we could schedule an interview. In the meantime, I’d been going online to review the growing body of television, radio and print available relating to Gordon: his appearance as a panellist on an episode of TVO’s Agenda titled “Reinventing Museums”; a guest on CBC Radio’s Metro Morning discussing, with host Matt Galloway, the recent announcement by the Art Gallery of Ontario (AGO) to sell off some Group of Seven art and make room for underrepresented artists; a CBC website video regarding his exhibition at Black Artists Network in Dialogue (BAND) called “Pried & Prejudice”.

In a short period of time, Gordon has become a “go to” with regards to questions of race and art in Canada, particularly Toronto. Gordon’s emergence as a spokesperson was not by plan, anymore than his emergence as an artist was by plan. Somewhere around 2012, Gordon started painting objects, specifically bowties which are something James wears almost every day. Then he surprised James with his portrait. With his partner’s encouragement, Gordon continued, choosing another object of fashion, this time shoes. Shoe paintings brought forth an intentionality from Gordon, the knowledge that viewers would be forced to draw their own conclusions about the sitter in the painting: race, gender, age, education, etc. After he began posting photos of the paintings on FaceBook the owners of a local coffee shop on Danforth contacted him. They showed the work of local artists, rotating on a monthly basis, and wanted Gordon to show his shoe paintings in an upcoming month. From there, Gordon moved to portrait painting and with that secured a spot at the neighbourhood Riverdale ArtWalk in the Jimmie Simpson Park. The feedback from other black men was immediate and positive, the fact they were “seeing themselves” in the portraits, black people represented as art subjects, front and centre, not as background in paintings by white artists.

As a self-taught artist who was slowly building a portfolio, Gordon had no previous interaction with the art community. What he encountered, in his view, was elitist, closed. “In his view” is important to note here, because whenever Gordon has been asked to speak, to represent, he makes it clear that he is bringing his view based on his experience. Increasingly, that experience includes interaction with young black people, especially art students, and it is their stories that motivate Gordon to be vocal about barriers and underrepresentation in the Canadian art world. In the last couple of years Gordon has been active engaging students at his alma mater, encouraged by Elizabeth (Dori) Tunstall, an African-American woman originally from South Carolina who, in 2016, became Dean, Faculty of Design at OCAD, a post that made her the first black, and black female, dean of a faculty of design anywhere in North America.

One experience with a black female art student both angered Gordon and, as he related the story to me, appeared all too familiar to him, commonplace. Gordon was at OCAD reviewing the portfolios of student illustrators, and a particular piece of work stood out for him. The illustration depicted a black man in a field, on his hands and knees, with sugar cane growing from his back. When he talked to the young woman about this piece she explained that she had been researching her family’s past, their history before coming to Canada, and her learning brought not only an understanding about her family but also the history of the “sugar economics” of slavery. Quite taken with the illustration, Gordon told her he thought it stood out as the best piece in her portfolio. Upon hearing that she explained that her white teacher had counselled her to remove it because of its controversial nature. According to Gordon the young woman rolled her eyes as she said, “Apparently he wants slavery to be cute.”

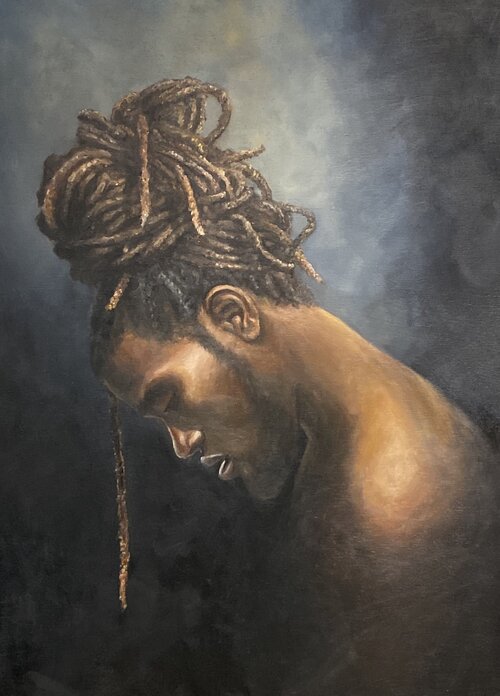

The reaction to his paintings, particularly from young black people and the stories they tell him of the racism they deal with, have propelled Gordon to create shows like “Visceral” (BAND exhibition, October, 2018) with portraits depicting subjects as they react in the moment to racist or biased comments and micro-aggressions. The show was a follow up to his 2017 “Pried and Prejudice” exhibition, that title’s pun signalling his exploration of the feeling of one’s life being “pried”, of constantly being watched, of being judged, as in being followed in a store because of the suspicion you might steal something. As I listened to Gordon I sensed, in some ways, these last few years as an artist have been a conversation of him with himself, his sorting out where he is at and where he has come from. He quoted two rather standard sayings from his parents that, yet, resonate strongly today. The first: “If you present yourself well you will be treated well.” Instruction from immigrant parents, black people even more of a minority in the Canada of the ’60s and ’70s. And yet, fifty years later, racial prejudice has not changed, no matter how well “they” have presented themselves — not when viewed from the eyes of a 53 year old black man born and raised in Canada.

The other familiar quote which guides him now: “If you’re not part of the solution, you’re part of the problem.” Unlike his father, Gordon has not entered politics but he has emerged as a leader as surely as he has emerged as an artist. Although Toronto is a world-leading multicultural city (especially to an old white guy like me) the racial divide seems not to be lessening. There are published statistics that black residents are 20 times more likely to be shot by police than white citizens. Within this milieu, Gordon paints portraits of young black men, wearing dark hoodies, staring straight ahead — straight at you if you are the viewer. What do you see? Or, more to the point, what are your emotions? Are you nervous, afraid? Why? What is unusual in the twenty-first century of a young man in a hoodie? Would your emotions be the same if it was a young white man in a hoodie?

As my thoughts return to the day I visited the ROM to see Gordon’s painting it strikes me how long ago it seems, though it was only in April, 2018. So much has happened, his brother’s unexpected death a few months later, our memorial birthday trip to New Orleans this past summer, and what feels like a surge of Gordon’s paintings, of Gordon’s presence in Toronto. I think, too, of the title of that ROM exhibition showcasing black Canadian contemporary art: Here We Are Here. Wherever Gordon Shadrach’s path leads in the next few years, that collective title will follow like an individual echo as he says: Here I Am Here. The reverberation of Gordon’s feedback to the world, his art a form of leadership in a distillation of subjects rendered in paint — and so bouncing back again, a feedback loop, from here I am to here we are. Leadership defined: from I to We.

To view Gordon’s paintings and find out how you can visit his studio space or purchase his art please visit his website.

The next Profile is the story of five creative, energetic women who revitalized a dormant branch of the Canadian Authors Association, creating exciting programs and tremendous support with Authors-Toronto.

I hope you come back.